I decided to participate in a study abroad program this summer with the recommendation of a friend. Last fall semester, one of my friends recommended me to study abroad since she had a great experience studying Spanish in Spain. I have always thought that I was already studying abroad in the US so I don’t need to study abroad again. However, I realized that staying with a host family was an experience I could only have before graduating from college.

Harvard does not have a language study abroad program in Japan, so students who want to study abroad in Japan need to apply to programs in other schools. There are primarily two programs that people apply to, one is the Kyoto Consortium for Japanese Studies (KCJS), and the other is Princeton in Ishikawa (PII). I chose PII over KCJS primarily because of its host family experience. I have heard that KCJS had host families in the past, but due to COVID-19, they stopped hosting students. I told some of my friends from Japan at Harvard that I was going to Ishikawa to study abroad. They told me that normally people don’t go to Ishikawa because there’s basically nothing there. That’s kind of true because walking out of my host family’s house, there’s nothing but fields of rice paddies.

After making my decision to study abroad Junior Fall, I enrolled in JAPAN BB (2nd semester Japanese at Harvard) in the Spring to brush up on my Japanese after the one-year stint I had learning Japanese at National Taiwan University (NTU) during the pandemic 2020 Fall – 2021 Spring.

The host family experience

The main reason why I chose PII over KCJS was due to the host family experience. I learned so much just by staying with a host family for 8 weeks. My host parents are about 70 years old and have been hosting students for about 20 years (I think I was his 17th PII student). There were several things I noticed being a host student.

The first thing was gender roles in Japan. My host mother would cook every day regardless of how late she came back. Most days we would eat dinner at around 8 pm. Both of my host parents work Monday to Saturday. During the host family-teacher conference, we also heard host mothers saying things like: “Why did their dad come? They don’t know anything that happens inside the house.” I would ask to do the dishes but my host mom would always tell me that she would do it herself. She also did laundry every 3 days. My host family was not the only family that operated this way–we soon realized that all of our host families operate like this.

I remember making a presentation on 輪島朝市 (Wajima morning market) and there was an article online that I asked my host mom about. The article said: “Grandmas would go to the morning market to sell things and close up the shop starting at 11:30 am.” My host mom told me that this is because women not only need to work (by having a stand in the morning market) but also take care of house chores after 12 pm. Therefore, the reason why it is only a morning market and not a whole-day market is because the grandmas need to go back home to do chores. She also jokingly told me that in the past my host dad would not do anything after coming back home. “Now, he does some stuff,” she said.

However, my host mom did mention that young people in Japan nowadays do not have such clear gender roles anymore. I am glad that Japan has worked toward equity between different genders. Taiwan also worked on this issue for a long time. I joked with my host mom that in my family, the first one to get hungry cooks dinner.

The second thing was how Japanese people are so proud of their nation. My host dad really likes to talk about Japan. For example, he would point at a tissue box and ask me if we have that in the US. I would always respond with: “Yes, we have tissue paper in the US, but maybe the quality is not as good as the ones in Japan. Most of ours are made in China.” Another time during dinner, he was talking about how he went to a few European countries as a host student in the 1990s1. He pointed to my plate and told me that at that time he wasn’t able to have such good food in Europe.

It seems as if my host dad was more interested in spreading Japanese culture than learning about different cultures in the world.

The Japanese view of contributing to society

Another thing I found interesting was my host family’s reason for hosting students. At first, I thought the main reason for them to host students was to keep the house more lively with students. They were old and most of their children had moved out. That is until I asked my host dad why he wanted to host students.

His reply took me by surprise: “国際貢献,” he replied. The term means “international contribution” in Japanese. He went on to describe how two atomic bombs were dropped in Japan, and how by hosting students, people from other countries could understand Japan more, thus reducing the chance of another war happening.

I think Japanese people have very interesting thoughts on how to contribute to society. At Harvard, most of the rhetoric surrounding contributing to society seems to focus on huge societal problems such as education, poverty, human rights, artificial intelligence safety, etc. From the Japanese people I have encountered, it seems like most of them choose to contribute by extending their skills to help others.

As an example, one of my Japanese friends in college is very good at playing the violin and wants to become a doctor in the future. I asked what her dream was. She told me how she really wanted to build a concert hall next to a hospital so that patients could easily listen to concerts. One of her relative’s dying wishes was to listen to a live classical concert, but there were not any near the hospital. So the wish could not be fulfilled.

Another example happened in JAPAN BB, which is second-semester Japanese at Harvard. Our teacher invited a famous そば (soba) chef in New York to teach us how to make soba. One of his goals is to spread soba everywhere, especially to less developed countries such as that in Africa. He mentioned the benefits of soba include: being easy to grow, gluten-free, nutritious, etc. One of his projects was to grow soba in the International Space Station!

I saw a lot of other examples in Japanese media. It seems like most Japanese people want to help people, however simple it seems. I’m not sure where this cultural difference comes from. Perhaps it is the Japanese language that forces people to think this way. Often times you are expected to “announce” what you are going to do before making an action. Perhaps the Japanese, like other Asian cultures, hold more collectivist attitudes, compared to the individualistic personalities of Western people. Perhaps many people in the US actually think they are contributing to society with their own skills, but are just seldom depicted in media.

Japan’s efforts to preserve history

Japan seems to spend a lot of time and effort in preserving history. In one of our excursions for PII, we got to experience playing the 尺八 (shakuhachi). This is a bamboo flute that originally came from China, but no longer played in China anymore. The origin of the 尺八 is still being investigated. According to a few online sources, while the original 尺八 was introduced to Japan in the middle of the 8th century, it was no longer played in the 10th century. During the 13th century, there was a resurgence of the instrument due to the Fuke sect of Zen Buddhism.

I found it very interesting how this instrument was originally invented in China (perhaps in India) and brought to Japan. While Chinese people no longer play it anymore, the Japanese were able to maintain the culture and create new techniques to play it. For example, with just five holes, one can still play all notes on the Western scale by using your fingers to cover half a hole. It seems as if you should go to Japan if you want to understand ancient Chinese culture.

Furthermore, during my visit to 兼六園 (Kenrokuen), I saw that the entire Japanese garden was maintained with constant manual labor. There were people crouching down picking leaves one by one in the fences. Everything from stacking the stone fences to removing weeds was done with manual labor.

This made me think about why the economy in Japan has not grown that much in the past two decades. While I am no expert on the Japanese economy, one reason might be the immense effort required to preserve history. Preserving history is pretty much only able to increase tourism. Putting the same effort into, for example, building factories may have a larger impact on GDP through increasing exports. Of course, one can argue the immeasurable intangible cultural value of having centuries of history in your backyard.

Differences between Japanese classes at Princeton and Harvard

The first difference between Princeton and Harvard’s Japanese classes is the choice of textbooks. Harvard finishes Genki I and II for 1st to 3rd semester Japanese and uses preceptor-compiled course packets starting from the 4th semester Japanese and beyond. Princeton uses Nakama I and II for 1st to 3rd semester Japanese and Tobira for 4th / 5th semester Japanese. I know that Princeton has their own preceptor-compiled course packet based on 千と千尋の神隠し (Spirited Away) for 6th semester Japanese based on my interactions with other 3rd year students at PII.

Nakama’s introduction to Japanese is more academic while Genki’s is more rule-based. Nakama would try to explain the different nuances of the language and the reasoning behind it. Genki, on the other hand, would just tell you: “If you want to convey this in English, then say this in Japanese.” To account for Genki’s deficiencies, Harvard’s preceptors would explain the rules in class. On the other hand, there were times when I would get confused about the explanations in Nakama and prefer Genki’s simple rule-based system. I think cross-referencing Genki’s textbook first and then reading Nakama’s explanation was important for me to understand the concepts.

The second difference is in Princeton’s classes, memorizing vocabulary was expected to be something students should do on their own. I do like Harvard’s version more where the preceptor goes through more difficult vocabulary in class and gives us opportunities to create simple sentences with the new vocabularylary. Extra information such as the origin of the vocabulary and 漢字 (kanji, Chinese characters in Japanese) also helped with memorization.

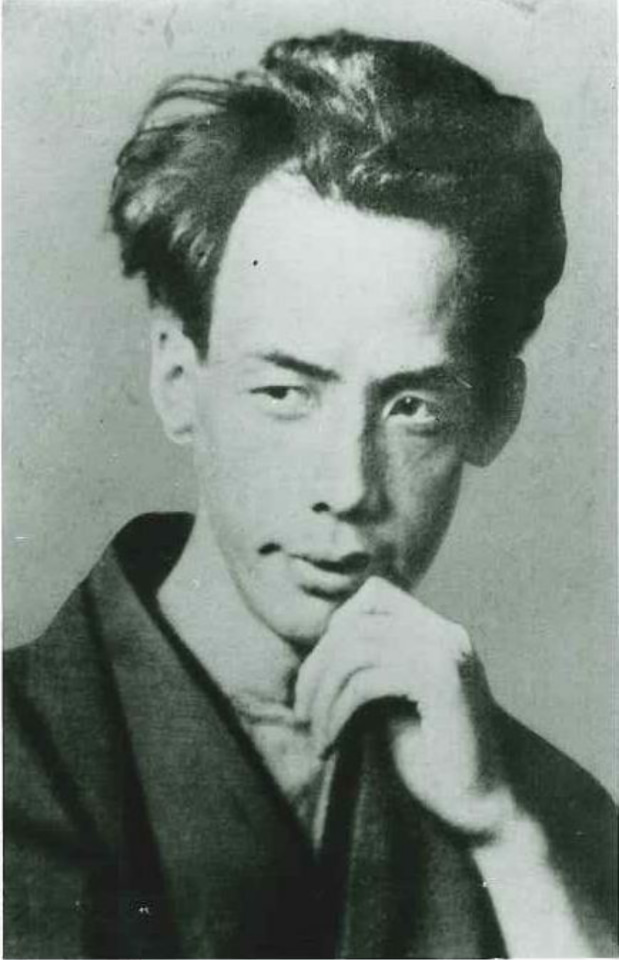

The third and major difference is in the 4th semester Japanese. Harvard’s preceptor-compiled packet contains famous essays that students in Japan would read in class. The 4th-semester Japanese packet seems to contain essays that elementary school students would read in class. For example, it contains 蜘蛛の糸 (En. The spider’s thread) by the famous author 芥川龍之介 (Ryūnosuke Akutagawa). I asked my host mom and she said that they had to read it in elementary school. Interestingly, the same essay also appeared in my high school Chinese textbook (local high school in Taiwan).

On the other hand, Tobira contains essays about different topics in Japan. For example, we had one chapter on Japan’s religion and another on Japan’s sports. The essays we would read were not famous essays in Japanese literature, but rather essays written by the editors of the textbook. I understand the organization of the textbook is to “learn Japanese culture” while learning the language. However, somehow learning Japanese culture through actual literary works that Japanese students would read growing up seems more natural and real. My goal to learn Japanese is also to be able to read Japanese novels in their original language so I would prefer Harvard’s course packet more. If Princeton could add some extra readings of Japanese literary texts would be also beneficial.

There was a question that popped up in PII: Should language learners learn about social problems in Japan? Or should they learn Japanese slang? In other words, for example, should we care about education in Japan? There was a chapter in Tobira on how the educational system works in Japan.

I do think it is useful to learn about how Japanese society works in general when learning the language. However, I do think it does not need to be the center of the essays we were reading. This is where the literature-based curriculum at Harvard shines. For example, I think it is acceptable to just learn a little bit of religion in Japan through the lens of an essay 蜘蛛の糸 (En. The spider’s thread).

In general, I am very glad that I have gone on this trip to Japan. I shall give thanks to my host family and teachers in Princeton. Also, thanks to Harvard’s Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies for their generous funding for me to study abroad. I would recommend other students to pursue a similar host family opportunity if possible.

Growing up being bilingual in English and Chinese, it has been a while since I had to learn a new language. I once again learned how difficult it is to learn a new language. There were many instances where I had to use Google Translate to communicate with my host family. All of this underscores the importance of maintaining humility in our lives.

- I’m not too sure about the year, but I think he said the 1990s. ↩︎

Leave a Reply